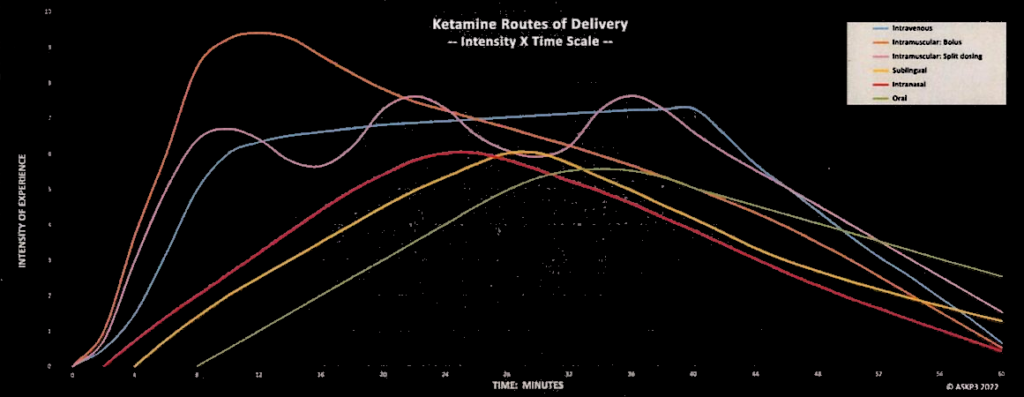

Introduction: Ketamine can be administered through various routes, each with unique advantages and disadvantages. https://www.askp.org/patients/routes-of-administration-roa/ Here, we will discuss the known ways of administration for ketamine. They are listed in order of bio-availability.

We will say more about bioavailability elsewhere. But briefly, bioavailability is essential for two reasons.

First, we want ketamine to have a therapeutic impact on the brain, and higher bioavailability means more ketamine reaches the brain. The extent of metabolizing and the resulting substances vary by ROA.

Second, we want ketamine to do its job on the brain with as little ketamine to be processed through the kidneys and liver. The greater the bioavailability, the less ketamine must be administered, reducing the potential stress on the urinary tract and liver.

IV – Intravenous Infusions: Most of the ketamine literature, both professional and popular, discusses IV almost to the exclusion of other ROAs. This is unfortunate because IV is the most expensive and least accessible ROA. You should understand IV ketamine notwithstanding that, for most patients, it is not the preferred first-choice ROA.

The drug is “infused” directly into the bloodstream through a vein, allowing for rapid/slow onset and precise dosing regulated by the flow of the IV drip. Or, more frequently, the rate of infusion is managed precisely by an IV pump. Once the physician chooses the dose for each patient for each infusion, a nurse begins a saline drip with a tiny quantity of ketamine slowly added. The effects are noticeable – termed the “come-up” – within a few minutes. Some patients experience this rapid onset of effects startling, at least initially.

The duration of the infusion is typically around 40 minutes. Time to prep, insert the IV, and remove the IV takes another 20 minutes. Rarely a patient (typically for pain) is prescribed a very long infusion period, from several hours to several days. The quantity dosed per hour is drastically reduced, while the total quantity infused over the protracted duration is much larger. Such prolonged, slow, high-quantity infusions are sometimes effective when a typical short-duration infusion has proven ineffective.

IV doses are customarily quoted in mg/kg of body weight. A typical dose is 0.5 mg/kg. So, a 150 lbs = 68 kg patient might receive a dose of 0.5 * 68 = 34 mg. The first dose or two is apt to be a little less; later doses are apt to be a little more. (Diagnoses for mental health are typically lower than those given for anesthesia, ranging from 1 – 4.5 mg/kg.)

The bioavailability of ketamine via IV is 100% by definition. All other ROAs have lower bioavailability.

IV can only be administered in a clinic; more about this is in the section on In-Clinic Administration. There are apparent advantages to IV in-clinic. The doctor and nurse have the most significant control over how fast the ketamine is administered. If the patient begins to have difficulty tolerating the effects of ketamine, the drug infusion can be stopped to mitigate the effects within a few minutes. The patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and oxygen level can be monitored regularly. All nice-to-have for the first few doses but less critical after the patient’s reactions to ketamine are well established.

Some patients seem to respond only to IV ketamine; other ROAs are less effective or not effective at all. So, while IV is usually not the first choice of ROA, it is usually a last resort for a patient who doesn’t respond to other ROAs.

The desired therapeutic response is the fastest via IV. This is important for patients who are actively suicidal (SI – Suicidal Ideation) or otherwise highly desperate for relief. In such cases, the cost and inconvenience of IV are justified.

IV infusions cost in the vicinity of $600 each. An initial course of treatment is typically offered as a package of, e.g., six infusions for a total cost of ~$3,000. When a clinic offers a new patient only a package price, the patient is faced with a sizeable financial commitment before he will know whether he is willing to tolerate the experience. The advantage is that the pre-paid financial investment encourages the patient to persevere in the hope that it will succeed and he will get his money’s worth. The disadvantage is that some patients won’t be willing to risk such a significant investment if they fear disappointment with the experience on the first or second dose.

Because the cost of IV infusions is so high, the prescriber must carefully balance the patient’s physical and psychological comfort in titrating up his dose vs. the patient’s financial interest in quickly getting to a therapeutic dose. Consideration of patient comfort argues for titrating doses up slowly. Consideration of patient economy argues for titrating doses up rapidly.

If the patient is suicidal or otherwise desperate, patient comfort must be discounted heavily. Conversely, sensitive patients are best titrated slowly, with great respect for comfort with the process.

IV (and, to a lesser extent, IM) seems to have a relatively long duration of effect compared to other ROAs. Patients in the maintenance phase often go 3 – 6 – 9 – 12 months between “booster” infusions after an initial 3- or 2-week course of therapy. After the initial “loading doses” twice a week, the patient transitions to maintenance. Weekly doses for a few weeks. Then bi-weekly, then every three weeks, every month, bi-monthly, and so forth. This is a notable advantage to IV for patients who find frequent dosing inconvenient.

Nausea is a common minor adverse side-effect of ketamine, especially by infusion. The prescriber will often administer another medication to mitigate nausea. Likewise, magnesium is also often included in the drip.

Ketamine is notoriously inconsistent in patient response from dose to dose. This is to say that a given patient, given multiple doses of the same quantity of ketamine by the same ROA, can expect very different experiences from each dosing. Why this is the case is not understood. But one of the variables is bioavailability. For example, a sublingual patient should do some oral preparation before dosing. Brush teeth, mouthwash, ginger/hot peppers/etc. Inconsistent preparation from dosing to dosing might account for some of the quoted variation from 25% to 30% in sublingual bioavailability. Because IV is consistently 100% bioavailable, at least this one variable is controlled by IV. Whether this is a significant advantage, we can’t say.

IM – Intramuscular Injections: This route involves injecting ketamine into the muscle, usually in the thigh or upper arm. While the onset is slower than IV administration, it is still relatively quick, with effects appearing within 5-10 minutes. IM administration is commonly used in emergencies or for patients with difficulty accessing a vein.

The bioavailability of IM is typically quoted at a flat 93%. We have not noticed any range of bioavailability quoted. So, IM shares with IV a consistency of bioavailability as an advantage.

IM injections in-clinic cost in the vicinity of $400. It is cheaper than IV infusions but still more expensive than at-home alternative ROAs.

IM injections are quoted in either mg/kg of body weight or in mg. So the figures noted above for IV are ball-park typical for IM doses.

Most IM is in-clinic; but a few practitioners are willing to prescribe at-home IM. Laryngospasm is a risk when administering ketamine by either IV or IM. A laryngospasm is a transient, reversible spasm of the vocal cords that temporarily makes breathing difficult. Onset is sudden, and it suddenly goes away in a few minutes. We suspect that the risk of a laryngospasm might be greater via IM than with IV because the IM dose is injected within a couple of seconds while the IV is “dripped” slowly.

A laryngospasm can be life-threatening if not resolved immediately by an attending physician. Incidence is reported as 0.46%, low, but as it is potentially life-threatening, it can’t be dismissed. When ketamine is administered in-clinic, a physician manages the problem. At home, there is no one up to the task. And so, laryngospasm risk is a compelling argument against at-home IM administration of ketamine.

Patients who don’t respond to the less bioavailable ROAs often respond to IM. There are a few reports of patients who did not respond to IV but went on to try IM and did respond. These anecdotes might be explained by the possibility that these patients were on the verge of responding to IV but gave up too soon. When they tried IM, they got the next dose that pushed them over to respond. An alternative conjecture is that the more rapid come-up of IV induced the therapeutic response.

SC – Subcutaneous Injections: There is very little published about subcutaneous injections of ketamine. In SC, the needle is inserted into the fatty tissue just beneath the skin, not deep into the muscle. This method has a slower absorption rate than IM or IV administration, which can result in a longer duration of action. Bioavailability is presumably about the same or somewhat lower as IM injections.

Nebulization Administration: We have seen no mention of nebulized ketamine for mental health patients. Nevertheless, there are reports of nebulized ketamine for analgesia in pain patients. The few studies show no long-term lung damage, and respiratory vitals remain high during treatment.

This ROA has a reported 70% bioavailability. As such, it is competitive with IM and likely more viable than IM. Until we see more reports of nebulized ketamine, we can’t offer more than this brief mention.

Nasal Insufflation involves spraying a saline solution of ketamine into the nostrils, which is absorbed through the nasal membranes. Nasal administration is an increasingly popular route of administration due to its ease of use and rapid onset.

Bioavailability is quoted at 50%. However, good reasons exist to question whether this figure might be high. How likely is it that ketamine transits the nose’s mucus membrane more effectively than the mouth or rectum? Perhaps the correct figure is 45% or 40% (pure conjecture, offered for illustration).

Another consideration is consistency. Bioavailability for SL or PR/PV is quoted as 25% – 30%, a wide range. If Nasal bioavailability were a consistent 40%, that modestly higher (supposed) figure would be notably better than the broader range figures for SL/PR/PV ROAs. (Again, pure conjecture, offered for illustration.)

Some patients object to the taste of lozenges. These may better tolerate nasal sprays.

Some patients have difficulty using the nasal ROA because of congestion. Others because a technique is required to keep the ketamine liquid in the nasal cavity rather than running down the throat or back out of the nostrils. Tip the head back a bit and spray a couple of spritzes, wait a few minutes, and do a few more.

Here, under Nasal, it’s important to point out that Johnson & Johnson’s (Janssen subsidiary) esketamine (trademark Spravato) product is only offered as a nasal spray. FDA regulations mandate that it only be administered in-clinic. Pharmacies compound racemic ketamine and can be prescribed for at-home administration. Not much nasal racemic ketamine is dispensed for at-home administration, but it is more than negligible/rare.

SL – Sublingual Administration: This route involves placing a ketamine lozenge under the tongue, where the drug is absorbed through the mucous membranes. This method is typically used for:

- maintenance (after an initial course-of-treatment in-clinic); or

- long-term treatment initiated at home.

The effects of the sublingual ROA are milder than IV and IM; however, the effects seem shorter in duration. Sublingual intervals between doses are typically much shorter than those for IV/IM. Initially, a sublingual patient will dose (typically) every three days, eventually stretching out intervals to once weekly and then to several weeks between doses. (IV/IM patients on maintenance will gradually increase intervals from a few weeks to a few months.) Why this should be expected is not clear. We have seen no studies showing this difference in duration to be true. It seems so from anecdotes published in the ketamine subReddits.

The SL ROA is ‘where it’s at’ in tele-ketamine for at-home administration. (IV is exclusively in-clinic, as is most of IM ketamine.) At-home nasal is not yet widely prescribed. So most at-home patients start with sublingual lozenges. A few of these migrate to PR/PV. Accordingly, this subsection is the place to begin your serious study of ketamine ROA.

Ketamine Drug Cost: It’s often the case that a compounding pharmacy charges a fixed price (whether that be $50 – $75 – $100) for a month’s prescription irrespective of the quantity per dose (100 mg . . . 400 mg) and irrespective of the number of doses (10, 15 or 30 per month). Other pharmacies charge different prices based on potency or number of units in the order.

The difference between the two pricing regimes may make very little difference if your prescription is for 10 lozenges per month and you are at a beginning dose of 100 or 200 mg/lozenge. Conversely, if you are buying a larger quantity or more potent doses then your order could be much cheaper if you find a pharmacy that does not price by potency or quantity of lozenges. It definitely pays to shop around numerous pharmacies to see how they price your particular prescription.

Bioavailability: Sublingual bioavailability is typically quoted from 25% to 30%. Occasionally, a quoted range is significantly lower, 20% or 16% or slightly higher, say 33%. Regrettably, whatever the actual figures might be, they are very low compared to every other ROA (except Oral, i.e., swallowing). Some of the variability is presumably due to individual biology. Some variability is presumably attributable to inconsistency in oral preparation (brushing the teeth, gums, tongue, and cheeks, alcohol-containing mouthwash, ginger/hot-peppers/niacin). Possibly, there are other, as yet unidentified, factors (conceivably fasting or diet, for example.) This disadvantage in low bioavailability must be offset by prescribing patients significantly higher doses compared to IV/IM.

Suppose a patient’s effective IV dose is 33 mg. That same patient’s sublingual dose might be 100 – 132 mg.

Another patient’s IV dose might be 100 mg; her sublingual dose might be 300 – 400 mg. For most patients, 400 mg twice a week won’t stress the tolerance of the urinary tract. Nevertheless, for very few patients, even such moderate doses have a non-zero potential to trigger ketamine cystitis. For further discussion, see the article titled “Urinary Tract – K Cystitis” under the Side Effects menu entry.

Arguably, patients prescribed relatively higher quantities of ketamine – such as 800+ mg/week – should consider asking for a prescription for a ROA with a higher bioavailability to reduce the quantity of ketamine load on the urinary tract while still delivering a therapeutic dose to the brain. Any patient who begins to experience urinary tract symptoms should immediately suspend dosing ketamine for a week and immediately consult his prescriber for instructions.

Compounding Pharmacies: Lozenges, suppositories and nasal sprays of racemic ketamine are produced by “compounding pharmacies,” not large pharmaceutical manufacturers. You probably do not have a compounding pharmacy in your neighborhood. Your prescriber will suggest one or more compounding pharmacies that they typically use. Even if you have a compounding pharmacy in your neighborhood, they may not offer ketamine. Or, if they do, their volume of ketamine sold may be so low that they might not be price-competitive with pharmacies with much larger production and sales volumes. (This is pure conjecture. One neighborhood compounding pharmacy I’ve found charges a little less than the most competitive national pharmacy I had been using.)

Compounding pharmacies produce lozenges in modest-size standard batches, e.g., some 100 mg lozenges, some 200 mg, some 300 mg, some 400 mg, and then pick-&-pack the prescribed doses per your doctor’s prescription. One pharmacy may produce doses of 100, 200, 300, and 400 milligrams; another produces doses of 150, 300, and 450. Your prescriber might recommend one pharmacy over another, depending on whether he wants you to have a dose of 150 vs. 100.

Each pharmacy uses its proprietary formulation of manufacture and filler. So, you might hate one pharmacy’s formulation but tolerate another’s. You can try another pharmacy if you don’t like your first pharmacy’s formulation. Before switching, ask your pharmacist what alternative formulations and flavorings they offer. If you don’t tolerate the first flavoring, you might try others to see if you can identify one you tolerate.

Shipping: Compounding pharmacies ship ketamine to your door via currier, two-day-air for a modest shipping charge, overnight for a substantial premium. DEA regulations allow the pharmacy to ship only a few days before the expiration of the previous prescription period. So it’s crucial that you make sure your prescriber calls in your new prescription a week or so before you will be out of stock and that the pharmacy fills and ships promptly so you will be re-supplied before you must take your next dose. Do not assume each new prescription will arrive on time like clockwork. Your prescriber is very busy with hundreds of patients. The pharmacy is busy with thousands of customers. Each prescription is unique to each customer. There are ample opportunities for error or delay, and you are the only one who will suffer if your prescription arrives late or is not quite right.

Because ketamine is a DEA Controlled Substance, there is almost zero allowance for a prescription that is lost. (The DEA is terrified that a patient with a legitimate prescription might give/sell his ketamine to someone else, claim it was lost, and replace the “lost” prescription with a new shipment.) Lost by the carrier, through porch piracy, or because your dog ate your prescription (along with your homework). If your month’s prescription is lost, expect to be without your medicine for that month. Suppose you can’t rule out porch piracy or trust your housemates to respect your ketamine. In that case, we suggest you arrange with a neighborhood business (perhaps a coffee shop or bakery) to receive and hold your ketamine currier packets for you to pick up personally.

Travel: If you travel regularly or rarely, you must plan for the possibility that you will be on the road when your monthly prescription ships. This can be a severe problem, so best to plan.

Your compounding pharmacy is probably licensed to ship to many states; but probably not licensed to ship to all 50 states, let alone all the US territories. A neighborhood compounding pharmacy is probably not licensed in multiple states unless it’s located near a bordering state. It can not ship outside the US. If you expect to travel to only a few states, you must ensure that your compounding pharmacy is licensed in those states. If you can’t predict which states you might travel to, select a pharmacy licensed in the most significant number of states.

You must personally take care to instruct your pharmacy to change your ship-to address for each order when you are traveling or returning to your home. Your compounding pharmacy will, almost certainly, keep your last shipping address on file and will ship to that address by default without necessarily calling you to confirm. They are not your travel agent, so they don’t know your itinerary. We recommend that you phone your pharmacy around the day you expect your prescriber to call in each monthly prescription to ensure no errors or delays. You absolutely must call your pharmacy if you need to redirect your next shipment to a different address. When you return home (or travel to a new location), you must call your pharmacy again to change your shipping address.

Troches vs. RDTs: Ketamine lozenges are typically produced in two forms: troches; or RDTs/ODTs.

A troche (pronounced “Tro-key” is typically a small tablet with a waxy surface coating. Often it is scored so that it can be easily broken into smaller units; e.g., a 200 mg unit could be broken into two 100s or four 50s. A troche tends to dissolve more slowly than an RDT, producing a slower onset of effects.

RDT is the acronym for Rapidly Dissolving Tablet. ODT is the acronym for Orally Disintegrating tablets. An RDT’s composition is like a grainy sugar candy; think of a cube of sugar, except that they are shaped into little cylinders. They are brittle and somewhat fragile. They are shipped in plastic trays of 10 or 12 lozenges. The trays are like toy cupcake pans with a paper “shipping label” seal to keep the lozenges in their cups. When you remove a lozenge, a little residual dust is left behind in the cups. An ODT’s composition is much more like an ordinary tablet than an RDT; however, it’s much more chewable than an ordinary tablet.

The distinction between the terms RDT vs ODT seems arbitrary. The characterizations described above are based on the terms and product composition of only two pharmacies this author has used and there is no reason to believe that other pharmacies adhere to the same terminology for the respective formulations. The difference between these compositions should be minimal to you as a patient. However, you might have a preference for one vs. the other.

RDTs, because they are so brittle, tend to disintegrate into dust in the shipping container or while handling. If you wish to take a smaller dose they tend to disintegrate while splitting them. You can bite-off half an RDT, but it’s difficult to bite off 1/4 of an RDT from half an RDT. But they dissolve rapidly without chewing.

ODTs, because they are not so brittle, don’t shed much dust in shipping or handling. They may be scored to facilitate splitting. They don’t dissolve so rapidly as RDTs, which you might prefer; they are more like troches in this respect. Yet, if you want the rapid onset of an RDT, you can chew an ODT.

Dosing / Split-Dosing: Sublingual doses can be as low as 15 mg (e.g., Joyous) to as high as 1,000 mg (e.g., Mindbloom). Your prescriber is apt to titrate your dose from a low to a higher level to accustom your brain to ketamine’s effects. After the initial titration period, typical doses range from 100 mg to 400 mg.

It is typically feasible to break a lozenge into halves to achieve a smaller dose, e.g., to break a 200 RDT into two 100s. It’s much harder to break a 1/2 into two 1/4’s. It’s easier to bite off a 1/4 “nibble” from a 1/2 “bite.” Acquire a few small containers with a secure cap to store fractions of an RDT for later use. The fractions outside their “cupcake” cup containers will disintegrate into dust. You don’t want to lose that dust. Your small container will hold the dust so you can dump it into your mouth after placing the fraction of the RDT under your tongue.

Your monthly prescription will be for lozenges of a particular potency, say 100 mg. Nevertheless, your prescriber will probably have you titrate your initial doses, beginning with a few (or many) smaller doses. This is one reason you must break up a lozenge into smaller pieces.

You may regularly take a small dose of ketamine while in session with your psychotherapist. If you took your regular full dose of ketamine immediately before a psychotherapy session, your verbal ability would probably be adversely affected. So, you must break up your larger doses into smaller “bites” or “nibbles” for dosing in-session with your psychotherapist.

Holding Time: The ketamine in a lozenge is mainly absorbed into the mouth in 30 minutes. Almost all is absorbed in 45 minutes. If a patient can tolerate holding the lozenge for 20 – 25 – 30 minutes without spitting or swallowing, that’s generally good enough. As the patient doses 3 – 6 – 9 times, tolerance for taste/saliva/numbing builds, and the patient will be able to hold for 25 minutes rather than 20; 30 minutes rather than 25. Consider the lower —> longer holding periods a part of the titration process.

Patients who well-tolerate taste/saliva/numbness often hold their saliva for 60 minutes or a little longer. That’s fine; a little more ketamine absorbed is better, but not significantly better. And there is no harm in holding as long as you like; Mindbloom patients excepted. Their recommended holding period is short, about 7 minutes; follow their specific instructions for you.

Taste: There is no accounting for taste among people for anything at all. This holds for ketamine lozenges. Troches seem to be a little less objectionable; RDTs are more objectionable.

Plenty of patients hate the taste of their lozenges. Most patients find lozenges perfectly tolerable. Compounding pharmacies try to cater to objecting patients by offering multiple flavorings in their lozenges, sometimes numerous flavorings. Unfortunately, a patient who hates one flavor is apt to hate others. There is no way to know whether any given patient who hates, e.g., the orange flavored lozenges will tolerate/or-not the cherry flavored lozenges. It’s purely a guess. (We wished that compounding pharmacies would produce a sample pack of dummy – zero ketamine – lozenges to ship to patients so they could try each flavor and rule-in/rule-out each labeled flavor. Unfortunately, we have not heard of any pharmacy that does this. Hopefully, this subsection might inspire pharmacies to offer such sample packs.)

Saliva, Numb Mouth: Besides taste, there are a couple of other less severe objections to lozenges. Ketamine provokes excessive saliva production. It also numbs the mouth. These two problems are more severe in the first few doses and taper off as the patient becomes accustomed to sublingual ketamine. However, objectionable saliva/numbing might last far longer than a patient can tolerate.

Prescribers typically instruct patients to hold a lozenge in the mouth for at least 30 minutes and preferably 45 minutes. (Mindbloom is an exception.) When taste/saliva/numbing is (are) intolerable, the patient can’t/won’t hold the lozenge nearly as long as instructed. He will want to swallow or spit, reducing the effective dose reaching the brain.

Alternatives to Taste/Saliva/Numbing Problems: Patients who can’t accustom themselves to taste/saliva/numbing usually switch to suppositories or nasal sprays. Suppositories might be somewhat objectionable from a usage perspective, but they avoid the taste/saliva/numbing problems entirely. Nasal sprays aren’t completely free of taste objections because a little spray can navigate to the mouth sometimes.

Spitting vs. Swallowing: Eventually, the saliva must go somewhere. The two alternatives are spitting or swallowing, each with its respective advantages/disadvantages.

The first thing to point out is that your prescriber may instruct you to spit, notably Mindbloom. For reasons not well understood, Mindbloom prescribes atypically large sublingual doses but limits the quantity of ketamine absorbed by instructing patients to spit after an unusually short holding period. It is very important to follow such spitting instructions to keep the quantity of ketamine absorbed into the body to a moderate level controlled by the short holding period. Otherwise (i.e., in the absence of prescriber instructions to spit), the following remarks are appropriate.

When excessive saliva production is problematic, a patient can spit some saliva into a small cup, holding the residual as long as possible. Once most of the ketamine in the residual saliva is absorbed, e.g., after 15 minutes, swallow/spit that (now-depleted) residual saliva and return the previously spit saliva to resume absorbing its still ketamine-rich contents.

Most sublingual patients swallow after holding for 30 – 45 – 60 minutes. There is a slight positive and a potentially significant negative to swallowing.

The slight positive is the opportunity to capture the last few milligrams of ketamine for absorption in the stomach and small intestine. There, the bioavailability is much lower than absorption through the mouth. Suppose it’s half (pure conjecture, for illustration). And suppose that 80% of the ketamine in a lozenge is absorbed in the first 30 minutes. Suppose a 100 mg dose. So, you are swallowing 20 mg of ketamine, of which – at best – 30% would have been bioavailable if it had all been absorbed in the mouth. That’s 20 * 30% = 6 mg; just 6 mg. Suppose those 20 mg are absorbed in the stomach at 15% bioavailability, 20 * 15% = 3 mg. So, swallowing allows you to capture just 3 milligrams more ketamine. Your mouth absorbed 80 mg * 30% = 24 mg. So, swallowing allowed you to gain just 3 / 24 / 100% = 7.2% more ketamine (compared to spitting). Not much.

The potential significant disadvantage is that ketamine might not agree with your digestive system. It might give you an upset stomach or nausea. It might extend your period of incapacitation by several hours. You will know only by trying. If swallowing ketamine disagrees with you, then spit. You aren’t losing much ketamine by spitting.

If you are inclined to try swallowing we suggest that you begin slowly. Spit the majority of your saliva after your desired holding period and swallow the minority. If you find the result agreeable, next time spit half and swallow the other half. If still agreeable, next time swallow all your saliva.

PR / PV – Rectal / Vaginal Suppository Administration: Often used when SL ketamine patients object to sublingual: taste; excessive saliva; numb mouth; or, compromised breathing function. It has a similar low bioavailability as the sublingual ROA.

Patients who choose PR are often enthusiastic advocates of this ROA. More so than might be accounted for simply by resolving taste/saliva/numbing/breathing objections to SL. Some patients insist they experience more robust responses from a consistent dose (e.g., they claim that 100 mg PR gives a better response than 100 mg SL). Whether this is true or not, we cannot say. We only mention these as anecdotal reports.

Much of the discussion above for SL – sublingual applies to PR/PV – Por Rectal / Por Vagina administration.

While PR is widespread, there is little mention of PV in professional literature or user blogs. Therefore, there is nothing more we can say about the PV ROA.

A patient who ultimately elects a PR/PV ROA will usually ask her provider to prescribe suppositories because they are more convenient than the alternative (described below). Note, however, that suppositories probably won’t lend themselves to split doses, e.g., to divide a 400 mg dose into two 200 mg doses. So, a patient who chooses suppositories should rule out the possibility of wanting to split doses. See the subsection on Dosing / Split-Dosing.

But how can a patient know if she prefers the PR/PV ROA? First, she will need to try the sublingual ROA. Only upon trying SL, will she discover she doesn’t tolerate taste/saliva/numbing. But she will still have 7 or 6 doses for the remainder of the month before getting the next month’s shipment in suppository form.

The workaround is to try a dose or two of PR/PV administrations using RDTs. It’s relatively feasible to crush an RDT into powder. Crushing a troche is doubtfully feasible. Add 1 ml of water to the crushed RDT and draw into a 1 ml syringe (without needle). Such syringes are cheap and readily available from Amazon overnight.

Lube the tip, insert 1/2 inch, and eject the solution into the rectum/vagina. If the PR/PV ROA experience is preferable to SL, ask your provider to prescribe suppositories for your next shipment.

Your pharmacy might have different pricing for suppositories vs. lozenges. If the differential is significant, you might prefer to crush RDTs and inject using a 1 ml syringe vs. the convenience of suppositories.

Oral (i.e., Swallowing) ROA: This route involves taking ketamine in pill or capsule form, absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract. However, the bioavailability of ketamine when taken orally is typically quoted as 16% – 20%, making it less effective than other routes of administration. We have seen no advocacy of oral/swallowing ketamine. It’s hardly worth considering at all.

Transdermal Administration: Rarely mentioned in the literature of any sort. Presumably, poor bioavailability. Rare mentions of bio-pharma companies working on transdermal “patch” products but none on the market to our knowledge.

Summary: This page highlights the various routes of administration for ketamine and their respective considerations for choice.

Intravenous (IV) infusion is the most commonly advocated and well-researched method, providing rapid onset of effects and precise dosage control. Relief is apt to be more immediate and of longer duration between booster doses. It’s justifiably considered the “gold standard” against which other ROAs are judged. Nevertheless, it’s the most expensive and least convenient considering travel to and from the clinic.

Intramuscular injections (IM) are highly competitive with IV, and subcutaneous (SC) might be a near-third. High bioavailability and long duration of action are big advantages. Expense and inconvenience are equally disadvantageous as for IV.

Intranasal ketamine has, at best, half the bioavailability of IV/IM/SC, but it is found to be better than the PR/PV/SL ROAs. Esketamine (Spravato) is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression, but there is little evidence it is more effective than racemic ketamine. And plenty of evidence that it is less effective. It is only available in-clinic, it’s expensive and transportation is inconvenient. Racemic ketamine is also available in nasal spray form and is cheap.

Sublingual administration, rectal and vaginal offer the lowest practical bioavailability but lend themselves to at-home administration. As such, they are the most consumer-accessible ROAs, and lower bioavailability is usually not problematic.

Oral (swallowing) ketamine has nothing positive to be said for it.

The choice of administration route depends on factors such as the patient’s medical history, condition severity, and treatment goals. Accessibility (in-clinic vs. at-home) will usually dictate or strongly influence the initial choice of ROA. Patient response and urinary symptoms may dictate a more bioavailable ROA.

Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (2019). Spravato (Esketamine) Nasal Spray [Prescribing Information]. Retrieved from https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/SPRAVATO-pi.pdf

Andrade, C. (2017). Ketamine for Depression, 4: In What Dose, at What Rate, by What Route, for How Long, and at What Frequency? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(7), e852–e857. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17f11738

Sanacora, G., Frye, M. A., McDonald, W., Mathew, S. J., Turner, M. S., Schatzberg, A. F., Summergrad, P., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2017). A Consensus Statement on the Use of Ketamine in the Treatment of Mood Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(4), 399–405. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0080

Mathew, S. J., Shah, A., Lapidus, K., Clark, C., Jarun, N., Ostermeyer, B., & Murrough, J. W. (2012). Ketamine for Treatment-Resistant Unipolar Depression. CNS Drugs, 26(3), 189–204. https://doi.org/10.2165/11599770-000000000-00000

Berman, R. M., Cappiello, A., Anand, A., Oren, D. A., Heninger, G. R., Charney, D. S., & Krystal, J. H. (2000). Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biological Psychiatry, 47(4), 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9

Sanacora, G., Frye, M. A., McDonald, W., Mathew, S. J., Turner, M. S., Schatzberg, A. F., … & Nemeroff, C. B. (2017). A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA psychiatry, 74(4), 399-405.

Rasmussen, K. G. (2019). Ketamine for depression, 3: does the route of administration matter? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(1), 18f12204.

Yang, C., Shirayama, Y., Zhang, J. C., Ren, Q., & Hashimoto, K. (2015). Regional differences in brain-derived neurotrophic factor and serotonin transporter binding among the antidepressant effects of repeated ketamine administration. Molecular psychiatry, 20(2), 157-164.